|

By accessing or using The Crittenden Automotive Library™/CarsAndRacingStuff.com, you signify your agreement with the Terms of Use on our Legal Information page. Our Privacy Policy is also available there. |

National Road, American Treasure

|

|---|

|

|

National Road, American Treasure

Ted Landphair

Voice of America

April 24, 2009

Pictures and Captions from 2011 version, The National Road

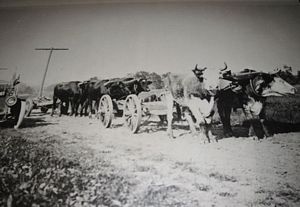

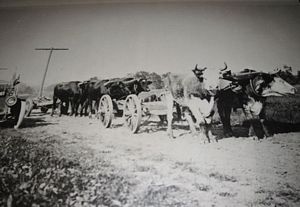

Travel on America’s early roads was, as the innkeeper Thenardier said in Les Misérables, “a curse.” (National Road/Zane Grey Museum) Travel on America’s early roads was, as the innkeeper Thenardier said in Les Misérables, “a curse.” (National Road/Zane Grey Museum)

George Washington commanded troops, if not slept, here, and this cabin in Cumberland is ground zero of The National Road. (Allegany County, Md., Tourism) George Washington commanded troops, if not slept, here, and this cabin in Cumberland is ground zero of The National Road. (Allegany County, Md., Tourism)

Here’s Doug, ready with a story about rudimentary early travel on The National Road. (Ted Landphair) Here’s Doug, ready with a story about rudimentary early travel on The National Road. (Ted Landphair)

The National Road doesn’t yet have as many trinkets, slogans, or fan clubs as U.S. 66 out West. But folks in Ohio are working on it. (Carol M. Highsmith) The National Road doesn’t yet have as many trinkets, slogans, or fan clubs as U.S. 66 out West. But folks in Ohio are working on it. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Signs old and new adjoin each other along the old road in eastern Ohio. (Ted Landphair) Signs old and new adjoin each other along the old road in eastern Ohio. (Ted Landphair)

Winding though it was, the National Road was an improvement over its rutted competitors. (Collection of Doug Smith) Winding though it was, the National Road was an improvement over its rutted competitors. (Collection of Doug Smith)

The Wheeling Suspension Bridge, over which The National Road still runs, looks its age, for sure. (Chris Light, Wikipedia Commons) The Wheeling Suspension Bridge, over which The National Road still runs, looks its age, for sure. (Chris Light, Wikipedia Commons)

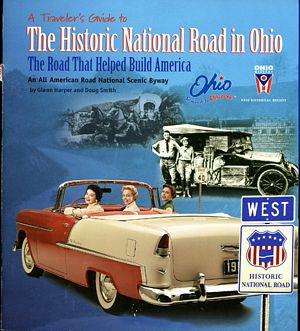

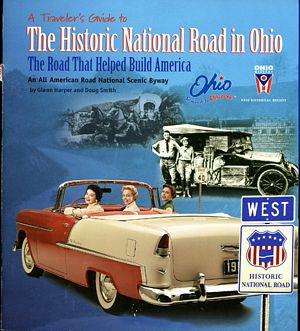

Doug and Glenn’s travel guide spans many generations of travel on The National Road. Doug and Glenn’s travel guide spans many generations of travel on The National Road.

In 1912, Congress ordered several “Madonna of the Trail” statues, including this one on the National Road in Ohio, erected along historic roads to salute westward-bound pioneers. (Courtesy, Cyndie Gerken) In 1912, Congress ordered several “Madonna of the Trail” statues, including this one on the National Road in Ohio, erected along historic roads to salute westward-bound pioneers. (Courtesy, Cyndie Gerken)

That’s a ordinary shoe, all right, between the pieces of wood in the braking device of an old Conestoga wagon. (Ted Landphair) That’s a ordinary shoe, all right, between the pieces of wood in the braking device of an old Conestoga wagon. (Ted Landphair)

This was one of the first toll booths travelers would have encountered on The National Road, near La Vale, west of Cumberland. (Allegany County, Md., Tourism) This was one of the first toll booths travelers would have encountered on The National Road, near La Vale, west of Cumberland. (Allegany County, Md., Tourism)

Here’s a short stretch of the Old National Road that had been paved in brick. Note how narrow it was! (Ted Landphair) Here’s a short stretch of the Old National Road that had been paved in brick. Note how narrow it was! (Ted Landphair)

One of the original National Road markers. (Ted Landphair) One of the original National Road markers. (Ted Landphair)

A classic, rustic barn along The National Road. (Carol M. Highsmith) A classic, rustic barn along The National Road. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Zanesville’s world-famous Y-bridge. (Andrew|W, Flickr Creative Commons) Zanesville’s world-famous Y-bridge. (Andrew|W, Flickr Creative Commons)

I was standing a part of the old National Road when I took this shot of U.S. 40 in the distance. My eye could also see the I-70 superhighway farther away, but it doesn’t show up very well here. (Ted Landphair) I was standing a part of the old National Road when I took this shot of U.S. 40 in the distance. My eye could also see the I-70 superhighway farther away, but it doesn’t show up very well here. (Ted Landphair)

|

Carol and I just got back from a fascinating drive along an interstate highway, parts of which are barely wider than a pickup truck!

It’s a highway, all right, just not a new one. And it was an interstate – in fact, the very first federal highway, begun in 1811, about 140 years before land was cleared for what we now know as America’s Interstate Highway System.

George Washington, the nation’s first president and a surveyor by trade, had fought French and Indian forces in western Pennsylvania, where the woods are as thick as bulrushes. Firsthand, he saw the difficulty of moving armies into the frontier, and he pressed for better roads than the old animal and Indian trails along which travelers struggled to move at the time.

Several short, earthen toll roads, or turnpikes, which were mired in mud each winter and spring and choked with dust much of the rest of the year, were cut between the port city of Baltimore on the Chesapeake Bay and Cumberland, Maryland, in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains. But far beyond those dense mountains beckoned the new “Northwest Territory” that began in Ohio. So in 1806, Congress authorized construction of what it foresaw as a sort of portage road between the Potomac River near Cumberland in the east, and the Ohio River at Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), far to the west.

Westward, Ho!

Beginning in a triangular park in downtown Cumberland at a little log cabin that had once been Washington’s headquarters, workers blazed westward along the old Nemacolin or Braddock Trail. Nemacolin was a Delaware Indian chief; Edward Braddock, a British general who had tramped that way, hoping to capture French forts.

But the “National Road,” as everyone soon called this remarkable pathway west, kept right on going, past Wheeling onto Zane’s Trace, a barely improved wilderness footpath to Zanesville in eastern Ohio. The target terminus, far to the west, was the mightiest river of all: the distant Mississippi. The National Road almost made it, stretching about 1,000 kilometers to Vandalia in central Illinois in the 1840s before funding ran out and enthusiasm waned. That’s because speedy, capacious new railroads stole the road’s thunder as well as most of its people and freight.

Carol and I learned a lot of this from Doug Smith, our enthusiastic guide and traveling companion on an exploration of remnants of The National Road in Ohio. Unlike the many train freaks and vintage-car enthusiasts, Doug, who’s a real-estate broker, Licking County commissioner, and auctioneer – you should hear him speed-talk through an auctioneer’s call! – just loves old roads. Until he and Glenn Harper, a founding member of the Ohio National Road Association, came along, most of the romantic stories of America’s historic byways had been lavished upon U.S. Route 66, which was created in the “roaring” 1920s from a string of state roads out west. Connecting Chicago to the Pacific Ocean via quirky crossroads and scenic desert byways, 66 has come to be known as “the Mother Road.”

If that’s so, The National Road, begun 110 years earlier, is wiry old Great Grandma.

“John Steinbeck and [the Great Depression novel] The Grapes of Wrath didn’t hurt the nostalgic craze over Route 66,” Doug Smith reminded me. Doug and Glenn Harper aren’t (yet) in Steinbeck’s league, but they have produced an exceptional little travelers’ guide that is a treasure trove of stories, vintage photos, and maps that help visitors locate, then enjoy, the many, though often hidden, delights to be found on The National Road in Ohio.

Carol and I wore out our copies, even as Doug told us stories and pointed out spots that we’d have never found on our own. And we ended up in one of the most curious, intellectually nutritious museums in America. Curious, as you’ll see, because of the odd combination of themes presented there.

All Aboard for Time Travel

I hope you like history as much as I do – and the wind in your hair as you drive with the top down! We’re gassed up and ready for a trip down The National Road. A smidgen of it, at least.

As I mentioned, The National Road winds from the ancient mountains of western Maryland to the pancake-flat plains of Illinois. Doug Smith’s neck of the woods in eastern Ohio is just a microcosm of an old road that teems with stories dating as far back as the opening of the American frontier.

Much of the way as you whiz past red, white, and blue signs for The National Road, you’re driving U.S. 40, a two- or sometimes four-lane federal highway that was given its number during the same era that Route 66 was strung together out West.

But those colorful signs reflect fiction as well as truth. U.S. 40 does follow the general path of the old National Road, but many of the most compelling remnants of the original, historic highway are little more than offshoots – driveway-size, even – running off that road into the woods or right up to somebody’s farm. If you didn’t have Doug Smith in the car with you, you wouldn’t know the real National Road was there. The original, narrow road twisted and turned, loped straight up gentle hills, and curled around steep ones. Come U.S. 40, the highway engineers of the 1920s were determined to proceed as straight as possible from Cumberland west, and they proceeded to widen, cut, fill, and pave over the old road to do it – chewing up, disguising, and discarding much of The National Road as they went.

Allow me to present nuggets from Doug and Glenn’s travelers’ guide, Doug’s genial tour, and my own peeks at roadside markers and overlooks.

Connections

Doug likes to tell about the Wheeling Suspension Bridge, across which The National Road finally spanned the Ohio River in 1849. Originally the world’s longest suspension bridge (at 308 meters), it twisted and torqued and finally collapsed into the river one day five years later, during a frightful storm. Everything but the structural engineer’s reputation survived. When it came time to rebuild, John Roebling, renowned for his Brooklyn Bridge across the East River in New York City, got the job. But the new Wheeling bridge got built only after city burghers upriver in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, stopped bellowing. They were worried that the workhorse steamboats of the period would not be able to pass under Roebling’s creation and deliver goods to Pittsburgh. Clever inventors averted the problem by figuring a way to tilt steamboat stacks backward on hinges, even at full steam, low enough to glide safely under Roebling’s bridge.

The National Road had first reached Ohio via smaller bridges, igniting a human flood so profound that, by the 1840 census, “frontier” Ohio had become the nation’s third-most-populous state.

Going in Cycles

And The National Road became its most popular thoroughfare. In their guide, Glenn Harper and Doug Smith include this note about the “safety bicycle” – the low-riding kind with wheels of equal size that we know today – that replaced scary, bone-shaking (and occasionally -breaking), 1.5-meter-high models that had been in vogue. The safety bike, the authors report, “brought new life to the old Road. To prove their physical prowess, young men would sometimes ride one hundred miles or more. Sherman Granger established a record in 1897 by riding his bicycle from Zanesville to Cumberland [337 kilometers] in four and one-half days. Such enthusiasts organized the League of American Wheelmen and in their quest for appropriate places to ride helped champion the ‘Good Roads Movement.’ Advocates for the movement increased dramatically with the invention and increased use of the automobile. In just ten years from 1900 to 1910, the number of automobiles increased from 8,000 to 468,000.”

That’s more than 58 times as many “horseless carriages” in a decade. And an awful lot of them rolled along The National Road.

I mentioned a most unusual museum. Called The National Road/Zane Grey Museum, it’s tucked up on a hill in little Norwich, Ohio. That’s enunciated as “Nor-wick,” not “witch,” in these parts, for reasons known only to denizens of the town. The museum, supported by the state historical society, displays three almost completely unrelated sorts of artifacts. One set, pertinent to our visit, explains The National Road. It includes a superb 41-meter-long diorama, displaying hundreds of tiny, hand-carved natural features, human figures, animals, wagons, tools, and road-building equipment – each individually crafted – plus other treasures and photographs related to the first federal road. The Zane Grey portion tells the story of America’s best-known Old West adventure novelist; he grew up nearby and was a great-grandson of Ebenezer Zane, whose “trace” we mentioned earlier. And there’s a wing devoted strictly to art pottery, which was once a thriving business in eastern Ohio.

Site manager Mary Ellen Weingartner pointed out three artifacts, in particular, that caught my fancy:

One was a “Gunter’s chain,” named after a 17th-Century British mathematician. Its 100 links, precisely, stretch exactly 66 feet (just over 20 meters). The men who blazed The National Road used Gunter’s chains to hew a uniform right-of-way as they went. The traveling portion was usually far narrower, as shallow drainage ditches and space for markers ate up part of the width.

The second notable artifact was an actual Conestoga wagon, which Mary Ellen described as the “semi truck of its day.” This was the pioneer freight wagon that you see in film “westerns” – the sort with billowing white canvas affixed to its high, arching ribs. Conestoga wagons, named after the Pennsylvania valley in which they first appeared, carried no drivers or passengers. They were pulled by 6 to 12 horses or oxen, but the drovers rode or walked alongside. The only seat was a short, hard, retractable “lazy board,” sticking out from the wagon’s side, on which an exhausted person could catch what must have been a short, incredibly uncomfortable ride. When these heavily laden “prairie schooners” headed downhill, a lever engaged a brake shoe to prevent the wagon from rolling over the dray animals that were pulling it.

I note this because a Conestoga wagon’s brake shoes were, in fact, real shoes! No doubt hand-me-downs that already had holes in their soles.

Look Out Below

Downhill travel on The National Road was indeed an adventure. Approaching a steep decline, a drover would sometimes stop, cut down a large tree, and tie it to the back of his wagon to slow the heavy, rolling loads. There’s even a slightly macabre marker along the Ohio portion of the road that pinpoints the spot where Christopher Baldwin became Ohio’s first known traffic fatality. On August 20, 1835, Baldwin, a Massachusetts antiquarian en route to central Ohio to study prehistoric Indian mounds, was riding “up top” with his stagecoach driver when they passed a pack of grunting hogs. The horses reared, the coach tipped over, and poor Baldwin broke his neck.

That third item of note at the National Museum/Zane Grey Museum is a series of rings that Mary Ellen Weingarten uses for school-group demonstrations. The rings fit around stones of various sizes, gathered in the area during an early upgrade of The National Road. It employed a mélange called “macadam,” developed in Scotland by John McAdam about 1820. A frame was laid ahead across the terrain, into which layers of carefully sorted stones, large ones underneath up to pebbles at road level, were spread, then compacted by a heavy, horse-drawn roller. No adhesives or fillers held these millions of stones together, Mary Ellen told me. The road was no longer a muddy path. It was all rocks, smooshed by that roller, then further compressed by passing wagon wheels and the feet of travelers and livestock.

That’ll Be 27 Cents

Both Mary Ellen and Doug pointed out The National Road became a toll turnpike once the federal government turned over jurisdiction to the states in 1835. Tollhouses popped up along the “turnpike.” (The word derives from the days when real pikes, or sharpened rods, across the road kept non-paying travelers from passing.) Travelers “coming down the pike” with those Conestoga wagons paid no toll at all, because the freight wagons’ wide wheels helped tamp down the road. Sheepherders were assessed 3 cents a score (20 head) for their herd; cattle – though nice and heavy – had sharp hooves that tore up the road, so their toll was 7 cents a score. Drovers took respite, and enjoyed a drink or two or ten, in roadside inns or in “pike towns” that sprang up along the road. Animal pens and barns corralled their animals.

In the 19-teens, engineers introduced still more new paving materials to The National Road. In places where brickyards abounded, row after row (after row after row after row!) of brick were laid. In fact, prison convicts completed an 80-kilometer stretch of brick from Zanesville eastward to Wheeling. Elsewhere, crews tried out various early forms of concrete. On some of those original road offshoots that you find off in the brush next to U.S. 40, you can walk on 95-year-old concrete and break off a stone or two where the surface has crumbled. To lay all that concrete, Doug Smith explained, narrow-gauge railways were created just for that job. They hauled sand and gravel and stones alongside the pavers, and as work moved on down the road, the rails were pulled.

Rest Only if You Must

Doug noted that there were rest areas along The National Road, just as you’ll find on today’s Interstate Highway System. There were certainly no information kiosks or giveaway maps, vending machines or men’s and ladies’ rooms, however. These turnouts offered only shade, a water well and pump, maybe a hard bench or two, and pit toilets.

Sometimes various layers of history converge along The National Road. Near the little town of Brownsville, for instance, a granite boulder at a place called the “Eagle’s Nest” was engraved in 1914 with the outline of a covered wagon and an early roadster automobile, as well as a written notation about the repaving of the highway. But attention is also drawn to the valley below, where the world’s first demonstration of contour farming was taking place at the same time.

Congress stipulated that markers be placed once in every mile along the road. Crews used their Gunter’s chain for that task as well; stretch one out exactly 80 times, and you had a mile. The sandstone mile markers, buried deep in the ground, carry a surprising amount of information, starting with the distance to Cumberland and including the names of, and distances to, the nearest towns. When these markers were broken by wayward vehicles or malicious vandals, concrete ones replaced them.

Other less formal sentinels of the old road are harder to find. Most period gas stations have been razed, turned into junk shops and the like, or modernized. Most, but not all, of the dreary little tourist courts, such as the “Nighty-Night Motel,” with their rows of identical rooms facing right onto the highway, are gone or empty relics. The clever Burma Shave shaving-cream ads that unfolded in four-line couplets plus a tag line on crude wooden signs . . .

Don’t stick your arm

Out too far

It might go home

In another car

Burma Shave

. . . are nowhere to be seen. But Carol was thrilled when Doug led us to a couple of classic, extant “Mail Pouch” barns, on which the chewing tobacco company’s distinctive logo had been carefully hand-painted.. In fact, Doug and Glenn Harper note in their travelers’ guide, a fellow named Harley Warrick from nearby Belmont, Ohio, painted hundreds of those signs on barns throughout the Midwest for half a century.

S as in Bridge

It’s hard to drag a “favorite favorite” National Road site out of Doug Smith. He loves every sign and pebble. But he’s awfully partial to the “S-bridges” that you can still see in a few places off U.S. 40. The bridge structures themselves are not S-shaped; that would be engineering folly. Like every bridge I’ve ever seen, save for one that I’ll tell you about in a moment, they shoot straight across the water at a neat 90-degree angle to the shorelines. But remember all those twists and turns of the original roadway? They brought The National Road up to many rivers at odd angles. So the early engineers had to maneuver the connections from the road to the bridge this way or that in order to line them up for a perfectly straight shot across. Taken together, the wiggly approaches and the ruler-straight bridge have the look of a big, snaky S. (You can see what I mean in the adjacent photos.)

My favorite stop was a pretty park, high above Zanesville. Below sat not just the town, in postcard splendor, but particularly a bridge over the intersecting Licking and Muskingum rivers.

That’s right: one bridge over the confluence of two rivers! It’s Y-shaped, the only one in the world, by Doug’s reckoning. For sure, it’s the only place we know of where you can go to the middle of a bridge and turn right! Early versions of Zanesville’s Y-bridge were even covered, like the quaint, though conventionally straight, covered bridges you see in Vermont or Indiana.

The National Road runs through two state capitals: Columbus, Ohio; and Indianapolis, Indiana, though you have to work to find it in both of those cities. Carol and I were both places on this trip but didn’t try very hard.

One of the treats of our ride along the old National Road occurred at a few spots where it was possible to stand on a fragment of the original pike, look across a field or up a hillside, and see two more generations of the road: U.S. 40 and today’s ultramodern, ultrafast Interstate 70. Not surprisingly, I-70 was the only busy one of the bunch.

In 2002, The National Road added a name when Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta designated it as “The National Historic Road.” That was rather a waste of effort. The “historic” part, as I hope Doug and I have demonstrated, goes without saying.

[Glenn Harper and Doug Smith’s The Historic National Road in Ohio: The Road That Helped Build America was published in 2005 by the Ohio Historical Society.]

Ted's Wild Words

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I’ll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of “Ted’s Wild Words” in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there’s another word in today’s blog that you’d like me to explain, just ask!)

Capacious. Large in capacity.

Denizen. Strictly, this means any inhabitant of a place. But the word also gives special status to animals and those of mystical powers, as in “denizens of the deep” or “denizens of the fields.”

Smidgen. A little bit. Sometimes shortened to “smidge.”

Travel on America’s early roads was, as the innkeeper Thenardier said in Les Misérables, “a curse.” (National Road/Zane Grey Museum)

Travel on America’s early roads was, as the innkeeper Thenardier said in Les Misérables, “a curse.” (National Road/Zane Grey Museum)

George Washington commanded troops, if not slept, here, and this cabin in Cumberland is ground zero of The National Road. (Allegany County, Md., Tourism)

George Washington commanded troops, if not slept, here, and this cabin in Cumberland is ground zero of The National Road. (Allegany County, Md., Tourism)

Here’s Doug, ready with a story about rudimentary early travel on The National Road. (Ted Landphair)

Here’s Doug, ready with a story about rudimentary early travel on The National Road. (Ted Landphair)

The National Road doesn’t yet have as many trinkets, slogans, or fan clubs as U.S. 66 out West. But folks in Ohio are working on it. (Carol M. Highsmith)

The National Road doesn’t yet have as many trinkets, slogans, or fan clubs as U.S. 66 out West. But folks in Ohio are working on it. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Signs old and new adjoin each other along the old road in eastern Ohio. (Ted Landphair)

Signs old and new adjoin each other along the old road in eastern Ohio. (Ted Landphair)

Winding though it was, the National Road was an improvement over its rutted competitors. (Collection of Doug Smith)

Winding though it was, the National Road was an improvement over its rutted competitors. (Collection of Doug Smith)

The Wheeling Suspension Bridge, over which The National Road still runs, looks its age, for sure. (Chris Light, Wikipedia Commons)

The Wheeling Suspension Bridge, over which The National Road still runs, looks its age, for sure. (Chris Light, Wikipedia Commons)

Doug and Glenn’s travel guide spans many generations of travel on The National Road.

Doug and Glenn’s travel guide spans many generations of travel on The National Road.

In 1912, Congress ordered several “Madonna of the Trail” statues, including this one on the National Road in Ohio, erected along historic roads to salute westward-bound pioneers. (Courtesy, Cyndie Gerken)

In 1912, Congress ordered several “Madonna of the Trail” statues, including this one on the National Road in Ohio, erected along historic roads to salute westward-bound pioneers. (Courtesy, Cyndie Gerken)

That’s a ordinary shoe, all right, between the pieces of wood in the braking device of an old Conestoga wagon. (Ted Landphair)

That’s a ordinary shoe, all right, between the pieces of wood in the braking device of an old Conestoga wagon. (Ted Landphair)

This was one of the first toll booths travelers would have encountered on The National Road, near La Vale, west of Cumberland. (Allegany County, Md., Tourism)

This was one of the first toll booths travelers would have encountered on The National Road, near La Vale, west of Cumberland. (Allegany County, Md., Tourism)

Here’s a short stretch of the Old National Road that had been paved in brick. Note how narrow it was! (Ted Landphair)

Here’s a short stretch of the Old National Road that had been paved in brick. Note how narrow it was! (Ted Landphair)

One of the original National Road markers. (Ted Landphair)

One of the original National Road markers. (Ted Landphair)

A classic, rustic barn along The National Road. (Carol M. Highsmith)

A classic, rustic barn along The National Road. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Zanesville’s world-famous Y-bridge. (Andrew|W, Flickr Creative Commons)

Zanesville’s world-famous Y-bridge. (Andrew|W, Flickr Creative Commons)

I was standing a part of the old National Road when I took this shot of U.S. 40 in the distance. My eye could also see the I-70 superhighway farther away, but it doesn’t show up very well here. (Ted Landphair)

I was standing a part of the old National Road when I took this shot of U.S. 40 in the distance. My eye could also see the I-70 superhighway farther away, but it doesn’t show up very well here. (Ted Landphair)