|

By accessing or using The Crittenden Automotive Library™/CarsAndRacingStuff.com, you signify your agreement with the Terms of Use on our Legal Information page. Our Privacy Policy is also available there. |

MOTOR RACING SPORT HOLDS ITS POPULARITY

|

|---|

|

|

MOTOR RACING SPORT HOLDS ITS POPULARITY

The New York Times

January 12, 1913

Game of Great Thrills Has Been Closely Bound Up with Automobile Development

EVENTS OF 1912 AND TO COME

New Contests Have Been Scheduled for Many Sections of the Country-Question of Control.

Despite the fact that novelty in automobile racing has worn away, leaving the utilitarian side of motoring far more important than the sporting features which distinguished the motor industry's early stages, competitions still thrill thousands of enthusiasts all over the world. After all automobile racing is, with the exception of aviation, the youngest competitive branch on the calendar of sport, and it combines all the elements of daring, speed, courage, and quick judgement.

|

Racing began almost at the birth of the industry, and as one record after another went by the board, the public, always ready for a new or novel diversion, quickly lent its patronage and support. The perfecting of the engine served to increase the public interest, as each succeeding improvement meant an increase in speed. Fortunately for the sport, it was safeguarded since its inception. Realizing its possibilities, responsible men were called upon to act as a controlling body. In this way rules and regulations were adopted and the races placed upon a sound basis.

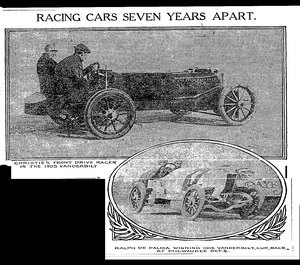

Manufacturers were not slow to recognize the value of racing as a means of exploiting their product, and this contributed to the development of the game. It was early demonstrated that mile circular dirt tracks were not adapted to its requirements, as the short curves made it impossible to get the best results in speed. The absence of motordromes made it necessary to bring forward road races. For speed purposes the closely packed sands at Daytona and Ormond were utilized, and surprising results were obtained. The success of foreign road races attracted attention in the United States, and the Vanderbilt Cup race was promoted. This was followed by the Grand Prize contest, copied from the road race held by the Automobile Club of France. The National Elgin, Fairmount Park, and other important contests followed. The Indianapolis Speedway was an innovation in that the spectators were able to watch the progress of a long distance race without losing sight of the competing cars. Los Angeles and other cities followed the example of Indianapolis and erected motordromes, and plans have now been drawn for a two-mile track near Hempstead.

After the investment of several millions of dollars, the race promoters enlisted the aid of the manufacturers, with a view to getting entries. This was the beginning of the real racing cars. Auto engineers were commissioned to design fast machines, and the assault on records began. The mile-a-minute car was considered a marvelous piece of mechanism, but this record was eclipsed, until Strang, in a 120 horse power imported car, traveled a mile in 37 7-10 seconds, the present record for the distance.

For many years foreign-built cars held all records in the United States. European makers had the advantage of several years' start, and this country proved a fruitful field for exhibiting their speed creations. As the industry expanded in America there was a noticeable improvement in the home product, and in a few years American racing cars were able to meet foreign machines on even terms. Meanwhile the Automobile Club of America and the American Automobile Association locked horns in an effort to control racing. The conflict was short. The American Automobile Association had the best of it. Then followed a systematic campaign to place all race meets under one control. The wisdom of this move was quickly apparent, as watchful officials represented the parent body at competitions and rigidly enforced rules which protected the public and compelled the owners, drivers, and promoters to live up to their contracts.

After passing through various stages, the real control of automobile racing finally reached the National Association of Automobile Manufacturers, which established a Contest Committee to work in connection with the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association. It was announced at a recent meeting of this committee that a spirited racing campaign would be inaugurated with the hope of restoring the various forms of motor car competition in this country.

The Motor Contest Association, which was composed of the leading car makers of the country, gradually assumed control and refused to lend its sanction to anything that did not benefit the commercial side of the racing proposition. Business played the "all star" part in all the deliberations of the association. The commercialization of racing, however, met its downfall. One by one the manufacturers abandoned their plans and withdrew from competitive events. Five firms remain in the field, but within the past three years these have either permanently retired or withdrawn temporarily.

The salvation of the racing game has been the amateur owner, who has replaced the manufacturer. These new supporters have entered their cars in competition more from a sporting standpoint than for pecuniary gain. Where the entries for races are made by individuals every one is competing on his own responsibility. Every contestant is out to finish first, and as a result the glory reflects on the owner and driver of the car rather than the maker. This furnishes a greater incentive to win and insures a better contest from a spectator standpoint.

The real, lasting value of racing to a manufacturer is an open question. Up to the last three years racing was in a great measure subordinated to commercialism. For years it was held that racing successes had much to do with establishing the popularity and prestige of a car. The actual performances of the winning cars were not counted as to their values from a competitive standpoint, but simply from the salesman's view. It was among these lines that the 24-hour races and long-distance contests were promoted, and the victories were measured by selling results. For years manufacturers spent hundreds of thousands of dollars in efforts to dispute the boasted supremacy of the top-notch cars of a rival organization.

From a trade standpoint the situation was apparently satisfactory, but the public were not considered except in so far as they contributed the funds to promote the contests. Special cars were built and advertised as stock cars, but none of the makers would consent to dispose of the racing car at the price asked in the show rooms for the regular stock cars. It was suggested that, in order to secure the confidence of the auto buying public, the racing cars be entered at a selling price similar to the entry of horses in selling races. This would have resulted in putting the winning car up at auction after the contest. But the proposition fell flat, as the manufacturers were not unmindful of the cost of building the car, which was frequently three times the catalogue price.

The excessive cost of conducting meets has been a source of considerable worry both to racing car owners and promoters. The expenses of building cars for the important track and road contests are little short of prohibitive. In many cases the cost of a single car reaches $5,000. With a battery of three cars $15,000 is tied up in the initial cost. The support of a crew adds another $5,000.

In 1913, as was arranged at the semi-annual meeting at Detroit recently, the manufacturers will be represented directly through their offices in the racing situation and management with the American Automobile Association. The Contest Committee of the National Automobile Association will give way to a committee composed of S. A. Miles and Alfred Reeves, representatives of the manufacturers. The manufacturers, however, are sound in the opinion that the American Automobile Association Contest Board should receive their hearty support, believing that the government of racing by a responsible organization like the American Automobile Association is absolutely necessary, and that chaos would result if the more or less irresponsible promoters and clubs were allowed a free hand in the promotion of racing.

It may be that the Contest Board of the A. A. A. will delegate its authority to District Superintendents and hold them responsible for the enforcement of rules and the management of races, the board acting as a clearing house for the entire country. For instance, in California there has been considerable trouble, and it is thought that a good deal of it could have been prevented if a representative of the board had been delegated with power to act in emergencies, with the right of appeal to the National Board in New York. This is the sort of government the National Trotting Association and the National Baseball League employ, and it seems to work well.

It has been suggested by A. G. Batchelder, Chairman of the Executive Committee of the American Automobile Association, that if a limited number of contests, geographically distributed and concerned with both speed and economy, could be arranged early in the Winter, it would bring forth something which might prove an effective supplementary accelerator to the industry, though of less degree than what has been accomplished by road building and the encouragement of touring. It is an admitted fact that a manufacturer would prefer to win a 500-mile or a 1,000-mile event with a limited piston displacement and an economy of gasoline rather than to please a large crowd, many of whom are attracted simply by the spectacular feature of the moment and a so-called victory with a monstrosity of an engine not on sale and not wanted by the average buyer. To continue exploiting, in hippodrome track races, cars of foreign make, with sanctioned supervision, is something that must be considered as well in the road contests.

In the annual report of the Contest Board of the A. A. A. for 1912 the Chairman, William Schimpf, points out that not a single instance of serious accident occurred throughout the year by either contestant or spectator in any event held under the sanction and official supervision of the board-a result never before attained in the association,s control of the sport. The death of Bruce Brown did not occur during a contest, but at the time the racing pilot was practicing for the Grand Prize race.

Many new records were established in the year, the marks from 100 to 200 miles on dirt tracks having been bettered, and in road-racing events the miles per hour average average of cars in former years over the same courses were invariably surpassed. Five hundred and seventy-two drivers were registered, of whom twenty-six were amateurs, showing a decrease from the 1911 registrations of 247, which was in large part due to the more severe restrictions imposed to eliminate inexperienced and incompetent drivers.

There is little doubt that 1913 will be ahead of any previous year in racing. The last 500-mile international sweepstakes at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway drew a bigger crowd than in 1911. The same is true of Santa Monica, Galveston, and Elgin. No less than five or six applicants are bidding for the Vanderbilt Cup race, which illustrates the demand for motor car racing. Regarding the 500-mile race, which has been changed from 600 cubic inch class to 450-inch class and under event, it is probable that a number of foreign racing stars will compete for the $50,000 in prizes. In this event they will remain for a series of meets, including Galveston, Elgin, the Vanderbilt Cup and Grand Prize races, and possibly Tacoma, Wash. There are projects under way for building new speedways at Seattle, Wash., or Portland, Ore.; also at Dallas, Texas. There will be more events on the Los Angeles Motordrome, and meets at Galveston, for which $50,000 will be hung up in prizes during the Cotton Carnival; also at Daytona, Old Orchard Beach, Santa Monica, and San Diego. Possibly the Fairmount Park road race will be revived.

The following list, compiled by the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, shows the list of fatalities in contests from Dec. 1, 1909, to March 1, 1912.

Thomas A. Kincaid, driver, killed in practice at Indianapolis, July 6, 1910.

Al Livingstone, driver, killed in practice at Atlanta, Nov. 1, 1910.

Ned Crane, driver, killed in practice at Kansas City, April 14, 1911.

H. P. Frey, driver, killed in practice at Brighton Beach, July 2, 1911.

Charles R. Robinson, driver, killed in practice at Brighton Beach, July 1, 1911.

Ralph H. Ireland, driver, killed in practice at Elgin, Aug. 21, 1911.

W. H. Pearce, driver, killed in practice at Sioux City, Oct. 10, 1911.

Jay D. McNay, driver, killed in practice at Savannah, Nov. 20, 1911.

H. F. Maxwell, mechanician to McKay, died Dec. 3 from injuries received.

W. H. Sharp, driver, (not registered,) killed in practice for Grand Prize race at Savannah, Nov. 10, 1910.

Tobin De Hymal, driver, killed in handicap event at San Antonio three-quarter-mile track, Nov. 12, 1910.

Marcel H. Basle, driver, killed in race at Hawthorne track, Chicago, June 10, 1911.

Richard D. Buck, driver, killed at Elgin race, Aug. 26, 1911.

Walter F. Donnelly, driver, killed in race at Milwaukee, June 21, 1911.

Sam Jacobs, mechanician, killed same place and date.

Matthew Bacon, mechanician to Harold Stone, killed in 1910 Vanderbilt Cup race, Long Island.

Charles Miller, mechanician to L. Chevrolet, killed in 1910 Vanderbilt Cup race.

Lewis P. Strang, driver, killed on Wisconsin State tour, July 20, 1911.

S. P. Dickson, mechanician, killed in 500-mile race at Indianapolis, May 30, 1911.

If present plans materialize, New York will have within the next year or two the finest motor speedway in the United States.