|

By accessing or using The Crittenden Automotive Library™/CarsAndRacingStuff.com, you signify your agreement with the Terms of Use on our Legal Information page. Our Privacy Policy is also available there. |

Here and There in Motoring's Past: Carl Fisher's Vanderbilt Cup Candidate

|

|---|

|

|

Here and There in Motoring's Past: Carl Fisher's Vanderbilt Cup Candidate

Peter Helck

Antique Automobile

March-April 1972

The Rejected Monster.

The Rejected Monster.

|

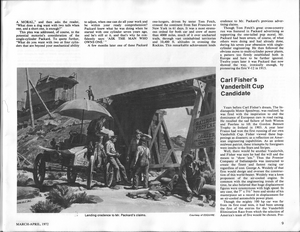

Years before Carl Fisher's dream, The Indianapolis Motor Speedway, was realized, he was fired with the inspiration to end the dominance of European cars in road racing. He recalled the sad failure of both Winton and Peerless to lift the Gordon Bennett Trophy in Ireland in 1903. A year later France had won the first running of our own Vanderbilt Cup. Fisher viewed these happenings as disasters; as a reflection on American engineering capabilities. As an ardent midwest patriot, these triumphs by foreigners were insults to the Stars and Stripes.

Well, there would be another Vanderbilt, and Fisher was sure he had the will and the means to "show 'em." Thus the Premier Company of Indianapolis was instructed to create the finest and fastest racing car regardless of cost. George A. Weidely of that firm would design and oversee the construction of this world-beater. Weidely was a keen proponent of the air-cooled engine. In common with the engineering trends of the time, he also believed that huge displacement figures were synonymous with high speed. In any case, the 7" x 5½" bore and stroke of his masterpiece set a record in displacement for an air-cooled automobile power plant.

Though the mighty 100 hp car was far from its first road tests, it had been among the first of the entries for the Vanderbilt Elimination Race from which the selection of America's team of five would be chosen. Presumably Mr. Fisher and all others involved in this sporting and patriotic gesture were informed of the official stipulations imposed on all entrants. However, when finally ready for the road, the naked, vicious-looking beast was found to be vastly beyond the internationally specified limit of 2204 pounds. With the race date on September 23, only eight days away, there followed desperate efforts to reduce poundage, one being the radical shift from bevel gear drive to that of double side chains.

Four days before the race, by which time some of the great European teams were arriving for the major race on October 14, the Indianapolis challenger (now less impressively stated as of 80 hp) had not yet arrived on Long Island. With the powerful foreign threat close at hand, came the announcement that Carl Fisher himself would drive his American entry, now rated at a modest 60 hp. Diminishing far less decisively was the Premier's tonnage. Frantic last-minute expedience necessitated the drilling of innumerable holes in its 136 inches of frame rails, its cradle bed for the huge engine and other structural supports. Alas, at the weighing-in the day before the race, Fisher's American hope failed to appear!

After the Elimination Race Fisher's characteristic obduracy was clearly demonstrated. The Premier Company ran full page ads telling of the appeal made to the Racing Board to run, on the pledge that upon gaining a place on the American Team, the car's excess weight—100 pounds—could be eliminated later to the complete satisfaction of officialdom. Obviously this audacious appeal had been rejected. And France again won the Vanderbilt.

The car exists today, a major showpiece in Tony Hulman's Car Museum at Indy Speedway, its myriad perforations and its chain-drive testifying to at least one Carl Fisher dream that failed of realization.

Topics: Carl Fisher, Vanderbilt Cup

Topics: Carl Fisher, Vanderbilt Cup

The Rejected Monster.

The Rejected Monster.