|

By accessing or using The Crittenden Automotive Library™/CarsAndRacingStuff.com, you signify your agreement with the Terms of Use on our Legal Information page. Our Privacy Policy is also available there. |

THE CHRYSLER SIX: America's First Modern Automobile

|

|---|

|

|

THE CHRYSLER SIX: America's First Modern Automobile

Mark Howell

Antique Automobile

March-April 1972

Many stirring words have been written about the golden classic period of the American automobile. Yet one of the most significant events of this fertile era has neither been fully presented nor completely chronicled.

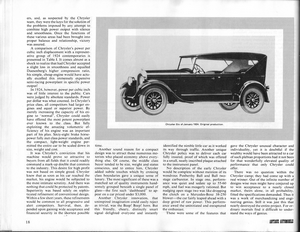

It is general knowledge that the last unknown American car capable of crashing our market and sticking was Walter P. Chrysler's compact little "six" that appeared back in 1924. But only those who have carefully studied production records of 1924 through 1927 can realize that this rather ordinary looking machine stands second only to the Model T Ford in its revolutionary impact on the industry. Beyond a doubt, this car stands alone as the dividing line between what may be termed "old" and "modern" cars.

Permit a moment's pause to dispel an old Chrysler myth that still lingers. Though developed and produced by the Maxwell-Chalmers Corporation, the new Chrysler was neither an up-dated Chalmers nor a "six cylinder Maxwell." Actually Chrysler and his associates designed the car with no outside help or direction. When the time came for production and development, Chrysler approached both Willys-Overland and Maxwell-Chalmers. The latter accepted his plans. Make no mistake, the Chrysler was a completely original conception.

When contemplating the period 1924 through 1927, it should be remembered that it was marked by the greatest affluence then known to America, plus a demand for cars that equalled the wildest dreams of the industry's leaders.

In 1924 there were 92 marques available, and, during that year, the combined Chrysler-Maxwell production earned 27th place. But three years later, the Chrysler Corporation had catapulted itself into 4th place. This represented extraordinary success, but not in itself proof of any revolutionary superiority. Furthermore, a closer look at the records reveals the staggering fact that during these same three booming years, 50 makes (or nearly 60% of the entire U.S. market) had failed and forever departed.

These failures were not confined to relatively unknown cliff hangers. Indeed, the commonly held belief that the great depression killed the majority of our most revered pioneers is quite untrue. Consider the following cars from various segments of the market: Haynes, Apperson, National, Winton, Cole, Mercer, HCS, Wills Sainte Claire, Templar, Westcott, Stephens, Lexington. Each had graced the scene in 1924 as an honored and integral part of the American culture, yet by 1927 all had faded into the limbo of past glory. And there were many more, of less character perhaps, but still household names in their time. All suffered the common conviction that fine materials and workmanship were more important than technical research and specialized knowledge.

It is unjust to place the burden of these boom time mass failures on Chrysler's superiority of appeal. Still, an examination of the mechanical specifications of those makes that did survive through 1928 and on into the depression reveals that the majority were those who were quick to discover and incorporate features that had made Chrysler and immediate success.

So what were the root causes of all this Chrysler charisma? Most authorities appear content to point out that Chrysler was the first medium-priced car to offer: (1) a high compression head and aluminum pistons; (2) hydraulic four-wheel brakes; and (3) oil and air filters.

Neither common sense nor record can attach much credence to these items. For example, Chrysler's compression ration was exceeded by 25 contemporaries, including Auburn, Moon and Oakland, all cheaper automobiles. And aluminum pistons were already standard equipment in the lower priced Essex and Oakland. Despite the superiority of hydraulic brakes, they remained highly suspect by the majority until the mid '30s. And as commendable as air and oil filters may be, they contribute little to the sales of automobiles. Obviously, Chrysler appeal flowed from other sources. But more about that later.

Let's take a look at market conditions in the early '20s, when Walter P. Chrysler first gave serious thought to designing a car to bear his name. It was the firm opinion of most contemporary authorities that the market could not absorb another medium-priced car. The segment was already dominated—even saturated—by such well-known stars as Buick, Hudson, Studebaker, Reo, Nash, Paige, Chandler, Jordan, Kissel, Haynes and Auburn.

This newcomer faced terrible odds. The Rickenbacker, for example, which appeared in 1922, was by prevailing standards an advanced design, and it was backed by the enormous prestige of "Captain Eddie". Yet it was never able to secure a firm foothold. And the 1923 Flint, offered by the famous W.C. Durant, suffered a similar fate.

Things had changed. In the past, the sound, new makes often succeeded for the simple reason that demand for well-known cars far exceeded their production. But now, with a multitude of familiar machines immediately available, the market was virtually closed to an untried and unknown make.

Chrysler the name was unknown to the public, but Chrysler the man had experienced vast success and prestige within the industry. Combining practical ability with extraordinary vision, he viewed market conditions in a wide perspective. Vividly aware of rapidly changing times, he noted deep rooted reluctance within the industry to make the proper adjustments.

Low-priced cars still offered little more than dependable transportation. Medium-priced cars conformed to mutually accepted limitations that inhibited progressive engineering. In the highpriced field, many of our finest machines, such as Locomobile, McFarlan, Pierce Arrow and Winton, were still basically 1910 designs. Even though these cars had impressive power, speed, smoothness and silence, the basis of this grandeur was a huge, inefficient engine which imposed costly and needless penalty in size and weight.

It appeared our cars of all classes were designed on the premise that America's economy was rural, its roads the worst in the world, and its people of an austere and Puritan outlook. Thus the poor should be satisfied with cheap, poor cars, the middle class with ordinary, drab cars, while only the rich should experience the joy of luxurious performance.

To Chrysler, this premise was no longer valid. World War I had industrialized the nation, and the population was moving to the cities. The economy was predominantly urban, whereas sophistication and affluence were on the upswing. A network of smooth highways was spreading across the land. The motoring public had become restless in its eagerness for something new and exciting.

How about a compact, medium-priced car with a combination of the more salient features of all classes? Wasn't the prime object of technical progress creation of a machine attractive to all?

Of course. But Chrysler felt that public acceptance of an unknown car would demand more than a well-balanced package of conventional values. In at least one of its functions, the car had to offer something of a sensational and unique nature. What single feature most endeared the motor car to the greatest number? Performance. Not merely as measured in power, speed and acceleration, but in the manner in which it was delivered. And the best means to make an unknown stand out above the old, familiar crowd was to endow it with a sharply elevated

quality of performance.

It was a great idea, but to translate it into reality was something else. For in spite of public hunger for exotic performance, experience had taught that wide acceptance demanded simple and conventional engineering. Twin overhead cams or blowers were out. Nevertheless, Chrysler decided that both public demands could and would be met.

Such a grandiose plan called for help of the very highest calibre. Chrysler was a shrewd judge of ability, and, while directing the rehabilitation of the crumbling Willys-Overland empire in 1920, had discovered a team of three young engineers eminently qualified to act as his associates. Fred M. Zeder, Carl Breer and Owen R. Skelton were brilliantly creative, and, equally important, energetic enough to keep pace with technical advances the world over. Fascinated by the depth and scope of Chrysler's dream, they jumped at the opportunity to play a part in its fulfillment.

Because the engine was to be the greatest single source of Chrysler's magic, the following almost impossible goals were set forth by the team: (1) power output relative to capacity had to border on the incredible; (2) the quality of silence and smoothness had to reach new frontiers; and (3) absolute simplicity of design had to be maintained to achieve minimal production costs.

Clearly this flew into the face of everything. It was common knowledge that the price of high output was noise and vibration, even with the most costly and complex design. To attempt to design and produce a cheap, L-head engine with such features was patently ridiculous!

Perhaps so. Chrysler did accept one costly feature—a fully machined, statically and dynamically balanced 7 main bearing crankshaft, but all else remained simple and straightforward, including side valves utilizing ordinary mushroom cam followers. And, when the great moment arrived for testing the engine, it fully met the objectives sought.

Had natural laws been circumvented? Not really. Through its own research and that of other pioneers, the Chrysler team had incorporated for the first time in an American engine the latest knowledge concerning combustion chamber design, fuel distribution, valve timing and cooking, cam contour (for silence), intake and exhaust manifold design, etc. These were the areas most neglected by other designers, and, as suspected by the Chrysler team, they were the keys for the solution of the problems imposed by any attempt to combine high power output with silence and smoothness. Once the functions of these various areas had been brought into proper balance and relationship, victory was assured.

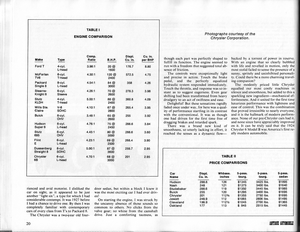

A comparison of Chrysler's power per cubic inch displacement with a representative group of 1924 contemporaries is presented in Table I. It comes almost as a shock to realize that had Chrysler accepted a slight loss in smoothness and equalled Duesenberg's higher compression ratio, his simple, cheap engine would have actually excelled this immensely expensive semi-racing powerplant in specific power output!

In 1924, however, power per cubic inch was of little interest to the public. Cars were judged by absolute standards. Power per dollar was what counted. In Chrysler's price class, all competitors had larger engines and equal or superior power. By merely increasing the capacity of his engine to "normal", Chrysler could easily have offered the most potent powerplant ever known to the class. But full exploiting the amazing volumetric efficiency of his engine was an important part of his plan. Sixty-eight brake horsepower fully met class power standards, and the compact, light-weight engine permitted the entire car to be scaled down in size, weight and cost.

It was Chrysler's conviction that his machine would prove so attractive to buyers from all fields that it could readily command a mark-up double that common to the industry. This desire for high profit was not based on simple greed. Chrysler knew that as soon as his car reached the market, his engine would be subjected to the most intimate scrutiny. And there was nothing that could be protected by patents. Superiority was based solely on sophisticated refinement of conventional design. Within a few short years, these refinements would be common to all progressive and alert competitors. Survival, then, depended upon gaining wide acceptance and financial security in the shortest possible time.

Another sound reason for a compact design was to attract those numerous motorists who placed economy above everything else. Of course, the middle class buyer tended to be size, weight and status conscious, and to entice him, Chrysler added subtle touches which by crossing class boundaries have a unique sense of luxury. The most significant of these was a matched set of quality instruments handsomely grouped beneath a single panel of glass—the first such "dashboard" to appear on a car priced under $3,000.

Another Chrysler innovation, that uninspired imagination could easily reject as trivial, was the Beep! Beep! horn. But this friendly, cheery, distinctly smart signal delighted everyone and instantly identified the nimble little car as it worked its way through traffic. Another unique Chrysler policy was to deliver each car fully insured, proof of which was offered in a small, neatly inscribed plaque attached to the instrument panel.

No description of the early Chrysler would be complete without its mention of its wondrous Penberthy Ball and Ball two-stage carburetor. In stage one, performance was quiet and sedate up to 55-60 mph, and fuel was meagerly rationed. But nudging open stage two was like dropping the clutch on Mercedes-Benz 38-250 blower—the car fairly leaped ahead with a deep growl of raw power. This performance awed the uninitiated and enraptured the enthusiast.

These were some of the features that gave the Chrysler unusual character and individuality, yet it is doubtful if the wealthy would have been attracted to a car of such plebian proportions had it not been for that wonderfully elevated

quality of performance that only Chrysler could offer.

There was no question within the Chrysler camp; they had come up with a real winner. Out of the infinite number of designs wise men might have conjured up to win acceptance to a nearly closed market, theirs alone, in all probability, fitted the specifications demanded. Thus it was a work of merchandising and engineering genius. Still it was just this that nearly destroyed the entire project. For ordinary mortals find it difficult to understand the ways of genius.

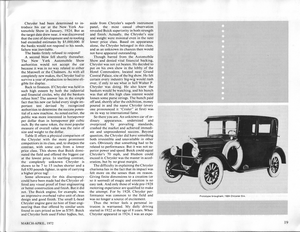

Chrysler had been determined to introduce his car at the New York Automobile Show in January, 1924. But as the target date drew near, it was discovered that the cost of development and re-tooling had exceeded estimates by $5,000,000. If the banks would not respond to his needs, failure was inevitable.

The banks firmly refused to respond!

A second blow fell shortly thereafter. The New York Automobile Show authorities would not accept the car because it was in no way related to either the Maxwell or the Chalmers. As with all completely new makes, the Chrysler had to survive a year of production to become eligible for display.

Back to finances. If Chrysler was held in such high esteem by both the industrial and financial circles, why did the bankers refuse him? The answer lies in the simple fact that his new car failed every single important test devised by recognized authorities to determine the success potential of a new machine. As noted earlier, the public was more interested in horsepower per dollar than in horsepower per cubic inch. By the same token, the most popular measure of overall value was the ratio of size and weight to the dollar. Table II offers a physical comparison of the Chrysler with the more prominent competitors in its class, and, to sharpen the contrast, with some cars from a lower price class. This shows that Buick dominated the field and offered the biggest car at the lowest price. In startling contrast, the completely unknown Chrysler is shown to be 7 to 15 inches shorter and a full 650 pounds lighter, in spite of carrying a higher price tag!

Some allowance for this discrepancy could have been made had the Chrysler offered any visual proof of fiber engineering or better construction and finish. But it did not. The Buick engine, for example, was an impressive overhead valve unit of clean design and good finish. The small L-head Chrysler engine gave no hint of finer engineering than that offered by similar units found in cars priced as low as $795. Buick and Chrysler both used Fisher bodies, but, aside from the Chrysler's superb instrument panel, the most casual observation revealed Buick superiority in both strength and finish. Actually, the Chrysler's size and weight were minimal even in the next lower price class. Based on appearance alone, the Chrysler belonged in this class, and as an unknown its chances then would not have appeared outstanding.

Though barred from the Automobile Show and denied vital financial backing, Chrysler was not yet beaten. He decided to put on his own show in the lobby of the Hotel Commodore, located near Grand Central Palace, site of the big show. He felt certain every industry big-wig would rush over, if only to see what in hell Walter P. Chrysler was doing. He also knew the bankers would be watching, and his hunch was that in all this high class interest would loosen some purse strings. The hunch paid off and, shortly after the exhibition, money poured in and the name Chrysler (every one pronounced it "Crisler" at first) was on its way to international fame.

So there you are. An unknown car of ordinary appearance, undersized and overpriced by prevailing standards, crashed the market and achieved immediate and unprecedented success. Beyond question, the Chrysler did have something both irresistible and unavailable in other cars. Obviously that something had to be related to performance. But it was not superior power and speed. Buick could equal Chrysler's 70 mph and Hudson could exceed it. Chrysler was the master in acceleration, but by no great margin.

The difficulty in explaining the Chrysler charisma lies in the fact that its impact was felt more on the senses than on reason. Giving finite dimensions to a creation (or so it seemed) of magic and emotion is no easy task. And only those of wide pre-1928 motoring experience are qualified to make the attempt. For by 1928, Chrysler performance was so common to the field and was no longer a source of excitement.

Thus the writer feels a personal intrusion is warranted. My daily driving started in 1922 at the age of 8 years. When Chrysler appeared in 1924, I was an experienced and avid motorist. I disliked the car on sight, as it appeared to be just another "light six", a type for which I had considerable contempt. It was 1927 before I had a chance to drive one. By then I was completely familiar with contemporary cars of every class from T's to Packard 8.

The Chrysler was a two-year old four-door sedan, but within a block I knew it was the most exciting car I had ever driven!

On starting the engine, I was struck by the uncanny absence of those sounds so common to others. No clicks from the valve gear; no whine from the camshaft drive. Just a comforting tautness, as though each part was perfectly shaped to fulfill its function. The engine seemed to run with a freedom that suggested total absence of friction.

The controls were especially light and precise in action. Touch the brake pedal, and the perfectly equalized hydraulic system responded immediately. Touch the throttle, and response was so instant as to suggest eagerness. Even gear shifting had been transformed from heavy drudgery to an act of swiftness and ease.

Delightful! But these sensations rapidly faded once under way, for here was a quality of performance startling in its contrast with the conventional. It was as though one had driven for the first time free of dragging brakes and retarded spark.

There was a brand new kind of smoothness, so utterly lacking in effort, it reached the senses as a dynamic flow—backed by a torrent of power in reserve. With an engine that so clearly bubbled with life and revelled in motion, only the most stolid failed to sense the presence of a sunny, spritely and uninhibited personality. Could there be a more charming traveling companion?

The modestly priced little Chrysler equalled our most costly machines in silence and smoothness, but added to this a sparkling new ingredient—mechanical effortlessness. And it united for the first time luxurious performance with lightness and ease of control. This was the combination that proved irresistible to nearly everyone, and it is the hallmark of modern performance. None of our pre-Chrysler cars had it, and none since have appreciably improved on it. It can be truly said that the 1924 Chrysler 6 Model B was America's first modern automobile.