|

By accessing or using The Crittenden Automotive Library™/CarsAndRacingStuff.com, you signify your agreement with the Terms of Use on our Legal Information page. Our Privacy Policy is also available there. |

Here and There in Motoring's Past: 1903 & 1955 - Cross Country Racing

|

|---|

|

|

Here and There in Motoring's Past: 1903 & 1955 - Cross Country Racing

Peter Helck

Antique Automobile

March-April 1972

This was his day.

This was his day.

|

On being asked to compare early racing accomplishments with those of a half-century later, Stirling Moss, most assuredly an immortal figure in racing history, replied with grace and mature perspective. Said he, "But there is no merit in comparison. THEIRS was the real achievement; brave men in the risky dawn of motor sport."

Firmly fixed in this writer's mind are two notable accomplishments, both dealing with cross-country racing in Europe, one "in the risky dawn," the Paris-Madrid of 1903, the other, five decades later, the Italian Mille Miglia of 1955. Within that span which endured two World Wars, automotive engineering had advanced from archaic crudity to a highly perfected technology. Aviation had become global and had largely replaced rail and other forms of surface transportation. Indeed, by 1955 we were on the threshold of the supersonic and space age.

When at daybreak on the morning of May, 24, 1903 the first of some 180 motor-powered vehicles of all sizes and categories were dispatched from Versailles to Bordeaux on the first stage of the Paris-Madrid, their past performances had rated the teams of Panhard, Mors and Renault as likely winners. Panhard had been scoring wins from 1896 on. Then in 1901 Henri Fournier had won both of the continental classics; Paris-Bordeaux and Paris-Berlin with his 60 hp Mors. In 1902 Marcel Renault had won the Paris-Vienna as Panhards placed second and fourth.

However promising the outlook was for these French marques there was a genuine threat posed by the new and somewhat hush-hush contenders from across the Rhine. These were the 90-Mercedes, six in number, with the renowned "Red Devil," Camille Jenatzy, heading the Teutonic sextette. Of the lesser-knowns, not too much importance was accorded the slightly-built tester, Fernand Gabriel. He was just an accredited member of the Mors team of ten, all driving the new 70's built for the race to Spain.

It seems needless to detail this tragic event in motoring's history. It has been reported and rewritten repeatedly as "The Race to Death" and needs no further dramatization or elaboration. Suffice to say that the little man driving the No. 168 Mors with its wind-splitting body shell thundered past innumerable splintered wrecks, overtook and passed some hundred or more hard-driving opponents in dusty hurricanes, and at no time knew his exact position in this mad procession. He was third to arrive at Bordeaux behind Louis Renault's No. 3 and Jarrott's Dietrich #1, both having preceded him by almost two hours in the starting order at Versailles.

Gabriel was a clear winner by 15 minutes. Over these 342 miles of unpatrolled highways, fraught with disaster for both participants and rash onlookers, he had averaged 65.3 mph, a mark so much in excess of all previous road records as to have been viewed as miraculous. It is still considered an epic performance by race historians.

The Government ended the race at Bordeaux. Enough blood had been spilled. As for the unassuming winner, never again did he come close to matching this sensational drive.

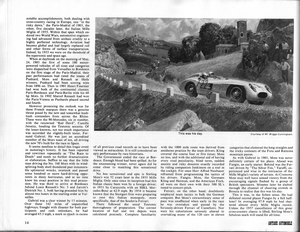

No less sensational and epic is Stirling Moss's win 52 years later in the 1955 Mille Miglia. Only once since its inception had this Italian classic been won by a foreign driver, in 1931 by Caracciola with an SSKL Mercedes-Benz at 62.9 mph. By 1954 it became known that the Stuttgart firm were preparing to oust this Italian monopoly, more specifically, that of the Scuderia Ferrari.

There followed the usual Teutonic thoroughness of preparation. The correct location of fuel and tire depots were calculated precisely. Complete familiarity with the 1000 mile route was derived from assiduous practice by the team drivers. Kling covered the course four or five times; Moss no less, and with the additional aid of having every road peculiarity, blind turns, sudden ascents and risky descents exactly recorded by riding companion Jenkinson on a reel in the cockpit. For once Herr Alfred Neubauer refrained from programming the tactics his drivers. Fangio, Moss, the Germans Kling and Herman, and the American Fitch, all were on their own with their 300 SL's tuned to concert pitch.

Ferrari, on the other hand, doubtlessly employed team tactics to balk the German conquest. But Moss's extraordinary sense of pace was unaffected when early in the race he was overtaken and passed by the furiously-driven Ferrari of Castellotti. Nor were his calculations seriously altered in overtaking many of the 120 cars in eleven categories that cluttered the long straights and the tricky contours of the Futa and Raticosa mountain passes.

As with Gabriel in 1903, Moss was never definitely certain of his place. Ahead was Fangio, an early starter. Behind was the Ferrari driven by "The Silver Fox," Taruffi, experienced and wise in the intricacies of the Mille Miglia's variety of terrain. At Cremona Moss may well have sensed victory from the encouraging signals flashed by a group of British spectators. Minutes later he dashed through the channel of cheering crowds in Brescia to realize that this was his day.

This it was, in the fullest sense. He had defeated second placer Fangio by a full half-hour! In averaging 97.9 mph he had shattered almost every Mille Miglia record. Unless the 1957 cancellation of this great cross-country classic is lifted, Stirling Moss's fabulous mark will stand for all time.

Topics: Stirling Moss, Mille Miglia, Fernand Gabriel

Topics: Stirling Moss, Mille Miglia, Fernand Gabriel

This was his day.

This was his day.