|

By accessing or using The Crittenden Automotive Library™/CarsAndRacingStuff.com, you signify your agreement with the Terms of Use on our Legal Information page. Our Privacy Policy is also available there. |

The American Automobile Industry that Almost Was

|

|---|

|

|

Topics: Tucker '48

Topics: Tucker '48

Opinions expressed by Bill Crittenden are not official policies or positions of The Crittenden Automotive Library. You can read more about the Library's goals, mission, policies, and operations on the About Us page.

|

The American Automobile Industry that Almost Was

Bill Crittenden

October 17, 2014

Investors' Brochure Investors' Brochure

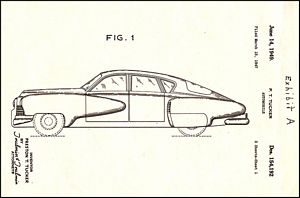

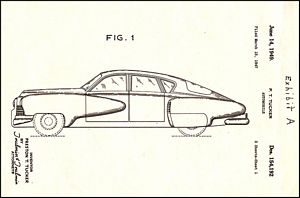

Design Patent Design Patent

1948 Tucker Sedan at the Blackhawk Museum, CC-SA 3.0 photo by Sean O'Flaherty 1948 Tucker Sedan at the Blackhawk Museum, CC-SA 3.0 photo by Sean O'Flaherty

|

I'm not an expert on the Tucker car. There are experts on it. You know that a marque with a total production of fifty cars has a loyal following over a half of a century later, it was something special.

But not a whole heckuva lot of the general automotive public knows the story behind the Tucker '48. One of the aforementioned experts could talk about this topic in incredible detail, for days, but here's an average fan of the car's summary of the story. Hopefully after this you'll be interested enough to learn more, and if you stick around until the end, I'll tell you a really fun way to do just that.

The car was just as much about the man who built it as the shape of the metal that went into it. Preston Tucker was an inventive Michigander with a penchant for automobile engineering. His start in the business was in 1935, when he teamed up with winning engine builder Harry Miller to design race cars for Ford to compete in the Indianapolis 500. He never saw any success, but his designs were later improved upon and ran with moderate success at the speedway for another decade.

His first great engineering success was the Tucker Combat Car. The U.S. Army wasn't interested so much in the armored car capable of 115 miles an hour, but the bubble top protecting the machine gunner interested them very much: it gained the name "Tucker Turret" and saw action in World War II on PT boats, landing craft, and the B-17 & B-29 bombers.

During the war, with no automobile industry to work in, he tried his hand at aviation, designing the lightweight Tucker XP-57 "Peashooter" powered by a Harry Miller engine. The airplane never got a production contract and never moved beyond the prototype stage, but its spec sheet suggests that the unarmored and highly maneuverable craft would have been an American equal to the Mitsubishi Zero.

Following a further failure in the airplane business after the XP-57, he moved back to Michigan to focus on the pending postwar business boom. Intending to reenter the automobile business, he designed a highly optimistic, forward-thinking automobile and began the process of taking it from drawing to production.

The car was to be radically different from any other on the American market. From the rear engine on a full-size sedan to the movable fenders that followed the wheels as they turned (and lit the turn ahead of the driver), it resembled the rest of the market only in that it had four wheels. But then each wheel was supposed to have its own torque converter for the smoothest ride possible at the time (an interesting idea, but it didn't allow for one key automobile feature: reverse gear!).

These technical details, while only drawn in artistic renderings used to attract investors (the fenders) or used on the prototype (the individual torque converters), would lead to the downfall of the company.

Having settled into the prototype and design process, it was realized that having the fenders move would make the car aerodynamically unstable, and a "cyclops" third light in front of the hood, the Tucker's most distinguished styling feature, would be linked to the steering and move left to right as the car was steered, lighting the way into a turn.

In the 1980's luxury cars would feature fender lights that lit left or right with the turn signal. Conventional in styling and engineering, it was nevertheless more than thirty years behind the Tucker.

The prototype was assembled from a junk chassis on a shoestring budget, earning it the nickname "Tin Goose." For budget reasons, also, war surplus flat-six helicopter engines were to provide the power for the original run of Tuckers. (Sound like a really big Porsche to you yet?)

One other feature that was VERY ahead of its time was the seat belt. Tucker wanted to make the car safe and include front seat belts. The conventional wisdom in the automobile industry at the time was that seat belts

implied that the car was unsafe. It wasn't until the creation of the NHTSA and the government mandate in 1967 that lap belts became a fixture on the American car.

After the prototype was successful and funding secured, a War Department program provided a factory in Chicago and the Tucker Corporation got to work. But not for long...

In the process of bringing this radical car from concept to production, Preston Tucker attracted the unwanted attention of Detroit's "Big Three." Anyone who knows the era well knows that competition in the car business wasn't always fair, or clean.

Rumors and speculation are that behind the scenes people were at work turning the investors and the government (Tucker was still in a government-owned factory and had conditions to meet, including a production deadline) against the automaker. Some of this was happening in Tucker's own offices as the people he brought in to turn a machine shop operation into a major manufacturing company were working against him.

In the end, the Tucker Corporation would meet its end in court. Despite producing a car as reliable as any ever built, they were judged on the junk prototype. Despite making a car decades ahead of its time, it was deemed not advanced

enough as it didn't include everything the original pitch to investors claimed it would. Despite making 36 cars by the deadline and bringing them to the court building to prove it, AND despite the court ruling in favor of Tucker, the factory was to be reassigned by the government to the Ford Motor Company.

The Ford name would stay on the building long after the government sold it, the building is now the Ford City Mall in the West Lawn neighborhood of Chicago, its connection to Tucker mostly forgotten.

The Tucker car, however, was far from forgotten. A total of 50 production models would be completed by the time the Tucker Corporation liquidated its assets, and just two have been completely lost due to fire and theft. The cars that aren't in private collections are in museums, and when one occasionally comes up for sale, they have gone from one to two million dollars at auction, depending on condition (of course).

There's even a controversial Tucker convertible, finished just a few years ago from an original Tucker frame and what are said to be Tucker's own original plans for such a car, but some doubt this. This story even has a Crittenden Library connection as Library advisor (and my father-in-law) John Walczak saw the plans in the seventies and swore in an affidavit that they bore the markings of original Tucker Corporation documents.

Want to learn more? In 1988, no less a man than Francis Ford Coppola would direct

Tucker: The Man and His Dream, starring Jeff Bridges in the title role! Even George Lucas, a Tucker owner himself, would be involved as producer. While not a box office success (putting it lightly-I credit that to limited interest in the subject), and some rewriting of the Tucker tale for dramatic effect, the film is a great way to spend an afternoon learning the basics of one of the greatest stories in the history of the American automobile industry.

Then spend the evening just sitting back with a drink and imagining how the industry, and the cars it produced, would have been different in the following decades had Preston Tucker gotten the chance he deserved.

Topics: Tucker '48

Topics: Tucker '48

Investors' Brochure

Investors' Brochure

Design Patent

Design Patent

1948 Tucker Sedan at the Blackhawk Museum, CC-SA 3.0 photo by Sean O'Flaherty

1948 Tucker Sedan at the Blackhawk Museum, CC-SA 3.0 photo by Sean O'Flaherty