|

By accessing or using The Crittenden Automotive Library™/CarsAndRacingStuff.com, you signify your agreement with the Terms of Use on our Legal Information page. Our Privacy Policy is also available there. |

Riding the Old Roads — and Reminiscing

|

|---|

|

|

Riding the Old Roads — and Reminiscing

Ted Landphair

Voice of America

July 22, 2011

Listen to Riding the Old Roads — and Reminiscing - MP3 - 2.9MB - 13:01

Listen to Riding the Old Roads — and Reminiscing - MP3 - 2.9MB - 13:01

Distinctive U.S. Highway signs had the look of police shields and, in places that could afford it, included reflective insets. (U.S. Highway Administration) Distinctive U.S. Highway signs had the look of police shields and, in places that could afford it, included reflective insets. (U.S. Highway Administration)

Even the amenity of color TV couldn't keep this old place along U.S. 66 in business. (Carol M. Highsmith) Even the amenity of color TV couldn't keep this old place along U.S. 66 in business. (Carol M. Highsmith)

This place on Route 11 in Virginia isn't exactly a snake farm. But it has the World's Largest Rattlesnake. Wonder who did the measuring? (Carol M. Highsmith) This place on Route 11 in Virginia isn't exactly a snake farm. But it has the World's Largest Rattlesnake. Wonder who did the measuring? (Carol M. Highsmith)

That cut-off loop of U.S. 66 is ALMOST deserted, but not quite. This charming vestige of yesteryear is in what's left of Hackberry, Arizona. (Carol M. Highsmith) That cut-off loop of U.S. 66 is ALMOST deserted, but not quite. This charming vestige of yesteryear is in what's left of Hackberry, Arizona. (Carol M. Highsmith)

This place, which looks like it did half a century ago, is still fully functional. (Carol M. Highsmith) This place, which looks like it did half a century ago, is still fully functional. (Carol M. Highsmith)

A toll house and an old, iron-wheeled wagon from the Plank Road days of the 1840s. (Carol M. Highsmith) A toll house and an old, iron-wheeled wagon from the Plank Road days of the 1840s. (Carol M. Highsmith)

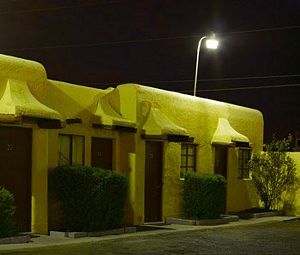

Motels along most of the old National Highways are quaint and one-of-a-kind. I'll leave it at that. (Carol M. Highsmith) Motels along most of the old National Highways are quaint and one-of-a-kind. I'll leave it at that. (Carol M. Highsmith)

|

There was once a Golden Age of automobile travel in the United States, when driving seemed carefree and scenic, and two-lane highways snaked across the countryside and right through the hearts of towns and cities.

No slick “bypasses” in those days. No siree. The whole point was to funnel travelers and their dollars right past local businesses.

Many of these routes had started as unmarked Indian trails and grown and grown until they got catchy names such as “Dixie Highway” — and then, in 1925, official U.S. highway numbers. Some, such as U.S. 66, the “Mother Road” about which many nostalgic books have been written, became the stuff of legend. It stretched all the way from Chicago to Los Angeles. Elsewhere, busy state roads such as Pennsylvania’s old Lincoln Highway were pieced together to form a road network that spanned the entire country.

The U.S. Government helped build and fix up these improved national roads, and crews tacked up thousands of shield-shaped signs with the highways’ numbers. At last you wouldn’t need 20 different maps to get from Ocean City, Maryland, to Sacramento, California. Just one U.S. road map, put out by Pure or Esso or Gulf Oil.

If you had spunk and a sense of direction, you didn’t need a map at all. You just got on the new U.S. Route 50 in Maryland and headed west.

Even-numbered national highways ran east-west — and of course, west to east as well. Odd-numbered ones cut north and south. Numbers for modern, high-speed Interstate expressways, which sucked much of the traffic off the old roads, work the same way.

Although Carol and I have cruised along Old U.S. 66 out W est three or four times as she searched for classic shots of old motels, coffee shops, and neon signs, I am partial to another national road closer to our Maryland home.

It’s U.S. Route 11, which I like to call the “French Connection.” It starts at Rouses Point, New York, on the edge of Lake Champlain at the Canadian border below Montreal and meanders down through Appalachian Mountain valleys before dipping into southern cotton country and fizzling out 2,700 kilometers (1,677 miles) away in formerly French Louisiana.

You’d expect such a Francophile highway, crusty with age or not, to conclude triumphantly in the heart of New Orleans’ storied French Quarter. Instead, Old 11 dead ends ignominiously at an east-west highway just outside of town. Instead of seeing the dancing lights of Bourbon Street, you confront a nondescript parking lot at 11’s terminus.

If the ride along it — through what has become the boonies — wasn’t bad enough, this is a deflating letdown.

Even in its heyday, U.S. 11 was never a sexy route. It was a narrow, workmanlike Canada-to-Gulf of Mexico highway, choked with trucks. Drivers endured it, then largely deserted it the minute the Interstate opened along its path.

In western Virginia, the cracked old highway wraps around I-81 so many times that, from the air, it must look like a snake on a beanpole. U.S. 11 intersects at several exits, taking traffic into towns, but disappears entirely for long sections where engineers simply straightened and widened it and turned it into the faster Interstate.

If you could take a pencil to Route 11, it would look like a Morse code message, with dashes and dots and long breaks along the way.

One sliver that I traveled much farther north, near Syracuse, New York, was still labeled the “Iroquois Trail” because its route followed an old Indian footpath up to Canada. The green, rolling country around it was once dotted with zinc, talc, and even salt mines.

In little North Adams, New York, 98-year-old Earl Timmerman recalled the days when Route 11 was the big deal, the haughty main road, lined with busy motor courts, drive-in-movie theaters, roadside diners, and produce stands.

Even snake farms and petting zoos and the world’s largest something-or-others.

“It was around 1911 or ’12 that they actually started putting in solid-top road, some form of material they put on the stones and made a solid base,” Timmerman told me.

In 1941, he and his brother-in-law opened an electric motor business in Watertown, 20 kilometers away. It could be a rugged commute up Route 11 in the region’s fierce winter blizzards.

About four of us rode together. We carried our shovels, and when we got stuck, we shoveled out. We could get out of the car and lay right down in the road and put the chains on, because we didn’t have to worry the least bit about anybody comin’ along and runnin’ over us!

That’s again just about the case on some stretches of Old 11 — and definitely so on parts of other disowned U.S. highways, including a long loop of U.S. 66 in northern Arizona that Interstate 40 completely bypassed.

“You remember the days of tourist cabins?” I asked Earl.

“’Course,” he said.

We had a place called Shady Rest, a series of little cabins, right out at the north side of Adams here. Quite a popular place. There was one drive-in movie. I guess the comin’ of television spoiled their business, and they closed down. Near Watertown, there was a little restaurant, and they specialized in hot dogs. And for the young people around town, the thing was to go and see how many hot dogs they could eat at night!

Fred Rollins, the executive director of Watertown’s historical society, recalled the days when the thousands of Canadian tourists heading to and from Quebec gave Route 11 a saucy international flavor. But like the old highway, Watertown has seen better days.

“Interstate 81 is now like the Nile of the area,” Rollins told me. “Everybody builds over there, and so the old public square of Watertown has had some hard times. We’ve lost so much of early Americana. If I have to go to Syracuse on business, I want to get there as quickly as possible. It would be fun to go through all the towns on Route 11, but we’ve become too much of a fast-paced society.”

He’s right. Who has the patience for traffic lights and speed traps and dingy hotels and food stands and motels and shops? Especially since the Route 11 “main drag” is now often in the decrepit “bad part of town.”

It once took an entire day to drive a slow-moving motorcar the 110 kilometers from Watertown south to Syracuse. You got your gasoline at drug stores, because gas stations had not yet been invented. If your car broke down, it was the local blacksmith who fixed it.

That stretch is the most famous part of the whole Route 11, however. L. Frank Baum, author of the children’s classic “The Wizard of Oz,” grew up in an oak grove there. His biographers say the spooky woods were the inspiration for the story’s Great Forest.

And it’s said Baum’s idea for the “Yellow Brick Road” that led Dorothy and her companions to the wizard came from a predecessor to Route 11. It was the nation’s first plank road, a 26-kilometer wooden turnpike reaching north out of Syracuse.

Robert Henry is the local historian and past president of the Plank Road Society. It maintains a charming park that features a model section of the thick, heavy, wooden planks that once lay side-by-side as far as the eye could see. “They were laid crossways on what were called ‘stringers’ — rails, if you will — embedded into the ground so they’d be nice and stable,” Henry told me. “The planks themselves were made primarily out of hemlock. It was strong, somewhat rot resistant.”

But not even the hardest wood could stand the pounding from the metal wheels of heavily loaded wagons for long, and the planks had to be replaced every five years or so. To pay for it, tolls of up to five cents were collected at four booths along the way.

Today you see a few sagging remnants of Route 11’s glory days — rusted tourist court signs pocked with bullet holes, vine-covered barns, long-shuttered restaurants, busted-up gas stations, chunks of old drive-in theaters, faded historical markers, and obscure museums where there’s not likely to be a wait to get in. On Old 11, you’ll find museums dedicated to hand weaving, American presidents, steam trains, even — in Scranton, Pennsylvania — the legendary magician and escape artist Harry Houdini.

Many of these places first opened at a time when people loved “the open road” and took great pride when a national highway ran through their towns. When roads got U.S. highway numbers, for instance, one from Bristol to Knoxville in eastern Tennessee received the coveted U.S. 11 designation, and a parallel road through the next valley was assigned the secondary-sounding “U.S. 511.”

Residents along the latter screamed bloody murder about it for two straight years, until Tennessee’s governor made a Solomonic decision: One road became U.S. 11E (for East) and the other, U.S. 11W. This calmed the locals but confused the dickens of out-of-state drivers passing through. Me, included.

In the northern reaches of Appalachia and in much of the South, too, Old 11 and the communities along it have pretty much gone to “rack and ruin.” Farms played out. Technology passed them by. Once-viable businesses were abandoned to the vandals and graffiti artists.

Increasingly rusted and rotted, the slice of America along Route 11 slid out of our daily lives.

“Disappearing America,” Carol and I call these places. They’re blemishes and nuisances to most, but feasts for a photographer’s — and a historian’s — eye.

Ted's Wild Words

These are a few words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word that you'd like me to explain, just ask!

Boonies. Also a Wild Word in an earlier posting, the boonies is short for “boondocks,” which in turn refers to remote, extremely provincial country. One theory of its origin is that American soldiers brought it back — Americanized from the Tagalog word "bundok," meaning “mountains” — from their deployment in the Philippines during World War II.

Dickens. A substitute for “devil” by those who are uncomfortable uttering anything to do with Satan. They prefer to say that something “scared the dickens” (or the daylight) out of them. The term has no apparent connection to British novelist Charles Dickens.

Ignominious. Lowly or disgraceful, inglorious. Worthy of shame.

Solomonic. Exceedingly wise. The term invokes the name of the biblical King Solomon who, most famously, found a way to determine the real mother of a baby who had been switched with an infant that died. Confronting two claimants, he raised his sword and announced that he would bisect the baby and give half to each. The real mother screamed and begged him to spare the child, even if it meant awarding it to the pretender. Clearly, Solomon decreed, she was the rightful parent.

Spunk. Spirit, determination, pluck.

Topics: United States Numbered Highways

Topics: United States Numbered Highways

Listen to Riding the Old Roads — and Reminiscing - MP3 - 2.9MB - 13:01

Listen to Riding the Old Roads — and Reminiscing - MP3 - 2.9MB - 13:01