International 500-Mile Sweepstakes Race (1911 Indianapolis 500) |

|---|

|

| Topic Navigation |

|---|

|

Return to Indianapolis 500

Wikipedia: 1911 Indianapolis 500 Page Sections Race Results Race Summary Article Index Jimmy Mullane at Indianapolis Other Images |

S.P. Dickson, the riding mechanic for Arthur Greiner, was killed in an accident. The list of those hospitalized for injuries includes Harry Knight, John T. Glover, C. L. Anderson, Arthur Greiner, Bob Evans, and David Lewis.

Race Results

May 30, 1911

Time of race: 6:42:02

Average speed: 74.602 mph

Margin of victory: 1:43

Pole: Lewis Strang (determined by order of entry)

Lead changes: 12 among 7 drivers

Lap leaders: Aitken (1-4), Wishart (5-9), Belcher (10-13), Bruce-Brown (14-19), DePalma (20-23), Bruce-Brown (24-72), Aitken (73-76), Bruce-Brown (77-102), Harroun (103-137), Mulford (138-142), Harroun (143-176), Mulford (177-181), Harroun (182-200)

Pace Car/Driver: Stoddard-Dayton/Carl G. Fisher

| Finish | Start | Driver | Car/Engine | # | Car Name | Laps | Avg. Speed/Status | Earnings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 | Ray Harroun* | Marmon | 32 | Marmon "Wasp" | 200 | 74.602 | $14,250 |

| 2 | 29 | Ralph Mulford | Lozier | 33 | Lozier | 200 | 74.285 | $5,200 |

| 3 | 25 | David Bruce-Brown | Fiat | 28 | Fiat | 200 | 72.730 | $3,250 |

| 4 | 11 | Spencer Wishart* | Mercedes | 11 | Mercedes | 200 | 72.648 | $2,350 |

| 5 | 27 | Joe Dawson* | Marmon | 31 | Marmon | 200 | 72.365 | $1,500 |

| 6 | 2 | Ralph DePalma | Simplex | 2 | Simplex | 200 | 71.084 | $1,000 |

| 7 | 18 | Charlie Merz | National | 20 | National | 200 | 70.367 | $800 |

| 8 | 12 | W.H. Turner* | Amplex | 12 | Amplex | 200 | 68.818 | $700 |

| 9 | 13 | Fred Belcher* | Knox | 15 | Knox | 200 | 68.626 | $600 |

| 10 | 22 | Harry Cobe | Jackson | 25 | Jackson | 200 | 67.899 | $500 |

| 11 | 10 | Gil Anderson | Stutz/Wisconsin | 10 | Stutz | 200 | 67.730 | |

| 12 | 32 | Hughie Hughes | Mercer | 36 | Mercer | 200 | 67.630 | |

| 13 | 26 | Lee Frayer* | Firestone Columbus | 30 | Firestone-Columbus | Running | ||

| 14 | 19 | Howdy Wilcox | National | 21 | National | Running | ||

| 15 | 33 | Charlie Bigelow* | Mercer | 37 | Mercer | Running | ||

| 16 | 3 | Harry Endicott | Inter-State | 3 | Inter-State | Running | ||

| 17 | 36 | Howard Hall | Velie | 41 | Velie | Running | ||

| 18 | 40 | Billy Knipper | Benz | 46 | Benz | Running | ||

| 19 | 39 | Bob Burman | Benz | 45 | Benz | Running | ||

| 20 | 34 | Ralph Beardsley* | Simplex | 38 | Simplex | Running | ||

| 21 | 16 | Eddie Hearne* | Fiat | 18 | Fiat | Running | ||

| 22 | 6 | Frank Fox* | Pope-Hartford | 6 | Pope-Hartford | Running | ||

| 23 | 24 | Ernest Delaney | Cutting | 27 | Cutting | Running | ||

| 24 | 23 | Jack Tower | Jackson | 26 | Jackson | Running | ||

| 25 | 20 | Mel Marquette | McFarlan | 23 | McFarlan | Running | ||

| 26 | 37 | Bill Endicott* | Cole | 42 | Cole | Running | ||

| 27 | 4 | Johnny Aitken | National | 4 | National | 125 | Out (Rod) | |

| 28 | 9 | Will Jones | Case/Wisconsin | 9 | Case | 122 | Out (Steering) | |

| 29 | Pole | Lewis Strang* | Case/Wisconsin | 1 | Case | 108 | Out (Steering) | |

| 30 | 7 | Harry Knight | Westcott | 7 | Westcott | 90 | Out (Accident) | |

| 31 | 8 | Joe Jagersberger | Case/Wisconsin | 8 | Case | 87 | Out (Accident) | |

| 32 | 31 | Herb Lytle | Apperson | 35 | Apperson | 82 | Out (Accident) | |

| 33 | 17 | Harry Grant | Alco | 19 | Alco | 51 | Out (Bearings) | |

| 34 | 15 | Charles Basle | Buick | 17 | Buick | 46 | Out (Mechanical) | |

| 35 | 5 | Louis Disbrow | Pope-Hartford | 5 | Pope-Hartford | 45 | Out (Accident) | |

| 36 | 14 | Arthur Chevrolet | Buick | 16 | Buick | 30 | Out (Mechanical) | |

| 37 | 35 | Caleb Bragg | Fiat | 39 | Fiat | 23 | Out (Mechanical) | |

| 38 | 21 | Fred Ellis | Jackson | 24 | Jackson | 22 | Out (Fire damage) | |

| 39 | 30 | Teddy Tetzlaff | Lozier | 34 | Lozier | 20 | Out (Accident) | |

| 40 | 38 | Art Greiner | Amplex | 44 | Amplex | 12 | Out (Accident) |

Race Summary

The following is text from Wikipedia as last modified on March 13, 2008, at 11:43.

|

The 1911 Indianapolis 500-Mile Race, or International 500-Mile Sweepstakes Race, the first recorded automobile race of such distance in history, and cause for the largest public gathering in the city up to that time, was held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on Tuesday, May 30, 1911. A departure from previous Speedway policy of holding numerous smaller racing meets during 1909 and 1910 racing seasons, the singular, large-scale event attracted widespread attention from both American and European racing teams and manufacturers, and, despite controversy surrounding its conclusion, proved far and away a successful event, immediately establishing itself as the premier motorsports competition in the nation.

One Race "Too much racing" After seeing a second decline in attendance in as many days for Labor Day, September 5, 1910, the final day of the concluding racing meet of the 1910 racing season at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, co-founders Carl Fisher, James Allison, Arthur Newby and Frank Wheeler conferred to decide on a new course for the following year. While the appearance on Monday of some 18,000 was reasonable enough in some respects, given both the rain showers occurring early that morning and the large parade held downtown in the afternoon, neither the two days of the Labor Day meet nor the July 4 weekend races had came near to equalling the 50,000 that had been attracted the previous Memorial Day. While potential explanations for the decline included the summer's extreme heat and the women of the city making holiday plans for their families that did not include auto racing, one of the most likely, they reasoned, was an overabundance of the very events they exhibited: too many races had diluted turnout to including only those most interested in the sport.[1] Timing and farming By the next day, Tuesday September 6, local newspapers had already picked up wind of the decision, and reported the four partners as considering, for 1911, a singular event with a purse high enough to attract global as well as local and national competition. Beginning with discussion of either a 24-hour or a one thousand mile endurance race as favored by several of the manufacturers, debate soon proceeded as to what would be most beneficial to spectators as well as participants; while a 24-hour event would be possible on a technical level despite its extreme nature, all agreed that potential ticket-buyers would inevitably depart the grounds well before its conclusion. Deciding on a "race window" extending from 10:00 A.M. to late afternoon, early estimates placed the planned race distance at 300 to 500 miles; the winner of the event, with purse estimates ranging toward $30,000, could expect to see as much as $12,000.[2] In choices for a specific date for the race, Memorial Day was always foremost. As suggested to the Speedway owners by Lem Trotter, the date coincided with the completion of a late-spring agricultural practice known as "haying," after which the farmers acquired an effective two-week break. While the intention, Trotter argued, would certainly be to draw from far more than just the local farming community, simple business sense dictated not interfering with fundamental aspects of the regional economy if possible. That such opportunity to avoid potential conflict of interest fell on a major national holiday sealed the decision: within two days, formal announcement was made of a 500-mile, marathon-distance motor race, to be held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, May 30, 1911.[2] Superlative As desired and expected, news of the inauguration of a contest of such distance evoked strong enthusiasm both within and without the motorsport community. Newspaper and trade magazine articles used ever-new superlatives for the challenges expected to soon face both drivers and engineers, and steadily continuing discussion throughout the spring and winter kept the race as the primary conversation piece of the comparative laymen of the street. Everyone, it seemed, had something to say about it.[3] Due to the publicity thus created, Speedway management, which had for the previous two seasons of meets charged the effectively nominal entry fee of one dollar per mile of scheduled race distances, took measure to ensure that the conceivably large entry list did not include any but the most serious participants: at an accordingly heightened fee of $500 per car, participation became a nominally risky proposition to teams and manufacturers, since, although the high finishers were due to receive record purse money and accessory prizes, no money at all was offered to finishers below tenth place. This did not seem to dampen interest, however, with entry blanks distributed over the course of the following month quickly returning filled, the first of which received from the J. I. Case Threshing Machine Compnay of Racine, Wisconsin, with Lewis Strang designated as driver of one of the company's Case automobiles.[3] The 500-Mile Race The largest racing purse offered to that date, $27,550, drew 46 entries from the United States and Europe, from which 40 qualified by sustaining 75 mph (120.7 km/h) for a quarter mile distance, though starting position was determined by date of entry instead of speed. Entries were prescribed by rules to have a minimum weight of 2,300 lb (1,043 kg) and a maximum engine size of 600 cubic inches (9.83 litres) displacement.[4] The cars lined up five to a row, excepting the first and last; the former led in what is now called the pole position by co-founder and president of the Speedway Carl G. Fisher in a Stoddard-Dayton pace car, the latter holding a single car to make up for the shifted positioning that resulted. Fisher's use of the Stoddard-Dayton is believed to constitute the first use of such a vehicle, for the first known mass-rolling start of an automobile race.[4] Amid roiling smoke, the roar of the 40 machines' engines, and the waving of a red flag which signalled 'clear course ahead', American Johnny Aitken, in a National, took the lead from the fourth starting spot on the extreme outside of the first row, and held it until lap 5 when Spencer Wishart took over in a Mercedes, himself soon overtaken by David L. Bruce-Brown's Fiat which would go on to dominate the first half of the race. Nearing the halfway point, Ray Harroun, an engineer for the Marmon company and defending AAA national champion, and the only driver competing without a riding mechanic due to his first-ever-recorded use of a cowl-mounted rear-view mirror, passed Bruce-Brown for the lead in his self-designed, six-cylinder "Marmon Wasp" (so named for its distinctively sharp-pointed, wasp-like tail).[4] Others falter during the marathon event; of the 14 cars to fall out, riding mechanic Sam Dickson is the lone fatality, killed when driver Arthur Greiner hits the wall in the second turn on lap 12.[4] Harroun, relieved by Cyrus Patschke for 35 laps (87.5 miles / 140.82 km), leads 88 of the 200 laps, the most among the race's seven leaders, to average a speed of 74.602 mph (120.060 km/h) in a total time of 6:42:08 for the 500-mile (804.67 km) distance to win.[4] Or apparently win. During the midpoint of the second half the race, Harroun and Lozier driver Ralph Mulford had fought an intense battle for supremacy, with Harroun being scored as holding a small advantage near the 340 mile (550 kilometer) mark...whereupon one of the Wasp's tires 'let go'. With balloon tires not yet developed, automobile tires of the day did not 'go flat', but were in fact thin strips of solid rubber which could be cut and torn without totally destroying the tire, and by extension the car, if pit stop for replacement occurred swiftly enough. Harroun's forced stopped allowed Mulford to move to the front, before Mulford soon pitted as well, also needing new rubber. After Mulford came back onto the track, Harroun was scored in the lead with a 1 minute, 48 second advantage...and it is on this statistic that controversy ensues. Upon Harroun's declared victory, Mulford filed protest, contending that he had lapped Harroun when the Marmon had limped in on the torn tire, an argument appearing plausible to some, due to an accident disrupting the official timing and scoring stand at nearly the same time. However, race officials were quick to note that Mulford's subsequent pit stop forced the Lozier crew to spend several minutes themselves changing a tire that had stuck to the wheel hub; Mulford's protest was thus denied, though the reality remains that the final result will always be open to dispute.[5] After the race, and collection of $10,000 for first place, Harroun returned to the position he had taken at the end of the 1910 racing season: retirement. He would never race again. Notes Race field average engine displacement: References and External Links Footnotes

[1]^ Davidson, Donald; Shaffer, Rick. "How It All Began: 1910", Autocourse Official History of the Indianapolis 500, Crash Media Group, Ltd., 2006, p. 26, 27. Retrieved on 2007-12-13.

Jaslow, Russel (1997). Who Really Won the First Indy 500?. Retrieved on 2006-06-16.

Copyright (c) 2008 Wikipedia.

Original document with more information at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1911_Indianapolis_500 |

|

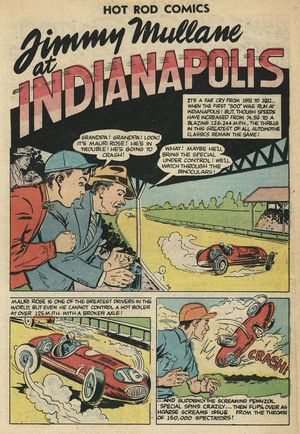

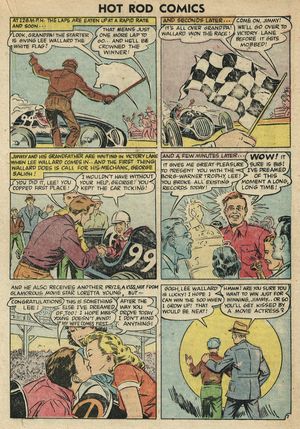

Jimmy Mullane at Indianapolis Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1, November 1951 View Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1 - 941KB |

|

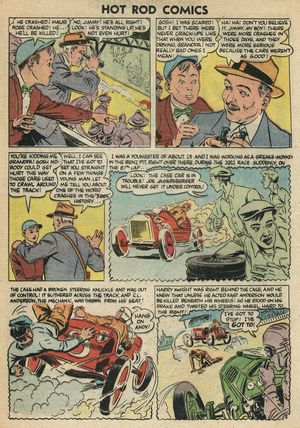

Jimmy Mullane at Indianapolis Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1, November 1951 View Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1 - 1.0MB |

|

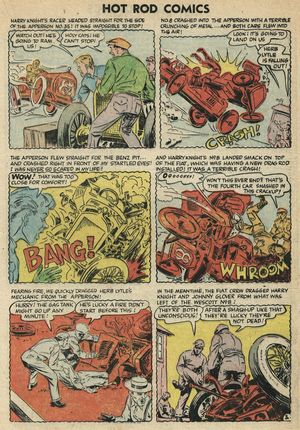

Jimmy Mullane at Indianapolis Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1, November 1951 View Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1 - 1.0MB |

|

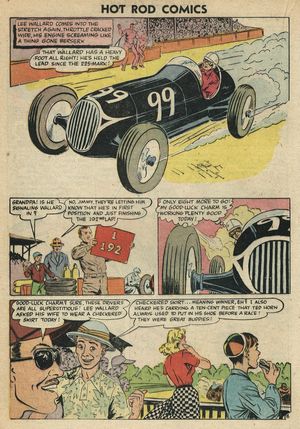

Jimmy Mullane at Indianapolis Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1, November 1951 View Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1 - 1.0MB |

|

Jimmy Mullane at Indianapolis Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1, November 1951 View Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1 - 1.0MB |

|

Jimmy Mullane at Indianapolis Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1, November 1951 View Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1 - 944KB |

|

Jimmy Mullane at Indianapolis Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1, November 1951 View Hot Rods and Racing Cars: Issue 1 - 1.0MB |

|

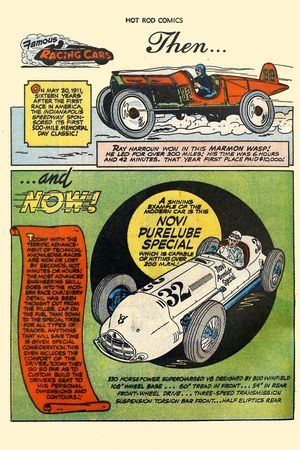

Famous Racing Cars Marmon Wasp & Chet Miller's 1951 Indianapolis 500 Kurtis Novi Purelube Special Hot Rod Comics #4, August 1952 View Hot Rod Comics: Issue 4 - 507KB |